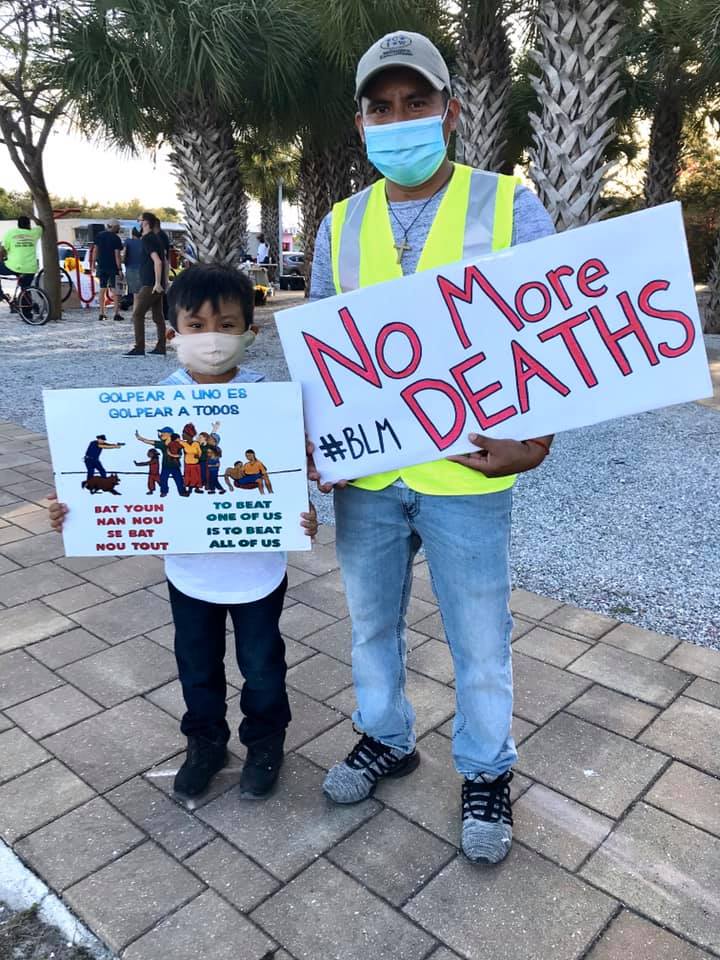

Signs bearing the words “To beat one of us, is to beat all of us” and “Justice for Nicolas” filled the corner of Immokalee’s Zocalo, a local gathering place. Nicolas was killed by Collier County police officer over 5 months ago. Nicolas’ vigil was attended by concerned and grieving community members and led by the Coalition of Immokalee Workers. Their statement regarding the death of Nicolas can be found here. https://ciw-online.org/blog/2021/02/as-he-lay-dying/ The young boy diligently holding up a sign towards the road during the two-hour vigil caught my attention. His dad, Wilson, an Immokalee resident, brought his whole family to stand in support of Nicolas. “It was important to bring my wife and children to support Nicolas’ family. We fear the safety of our family and for others in the community who are just trying to get by. There are times when we leave the house late to get medicine or other necessities. How do we know we can feel safe? The police are supposed to protect us. I don’t know what they may think of us as farmworkers, but not all of us are here to do wrong. We aren’t all who they say we are. Farmworkers come to work here and have families to protect. His death wasn’t fair to him or to his family. He may have been going through some mental health issues at the time of their encounter based on his behavior. It could have been resolved differently. All we’re asking for is to be treated with dignity and respect. Justice would be knowing that our lives would be valued and what happened to Nicolas, would not happen again. The police officer didn’t value his life and it was shown by his actions.”

0 Comments

For many whose life began in another country, there are comforts and traditions that keep them connected to their motherland. Jean, a local resident, describes how he’s still finding hints of home even in the midst of a pandemic through his daily routine. “In Haiti, this is what I was used to. There weren’t any formal markets where I grew up. Traditionally, street vendors called 𝑀𝑎𝑐ℎ𝑎𝑛𝑛 passed by daily and we got what we needed for the day. Even though I’ve been gone from Haiti for so long, we are used to 𝑀𝑎𝑐ℎ𝑎𝑛𝑛 passing by the apartments. Nowadays the only person who walks by is the 𝑀𝑎𝑑𝑎𝑛 𝑆𝑎𝑟𝑎, a woman street seller that sells fresh food and vegetables. Everyone else stopped because of the virus. Sure I can go to the store, but I support her because she’s been selling around here for decades and I trust her products. Everyone around here knows her and she’ll let us buy with credit if we don’t have the money. If she doesn't have what I need, I’ll go to the local farmers market. The 𝑀𝑎𝑑𝑎𝑛 𝑆𝑎𝑟𝑎 coming around reminds me of home. Today I bought 𝘱𝘸𝘢𝘳𝘰 (green onions), 𝑙𝑎𝑦 (garlic), and 𝘴𝘪𝘵𝘸𝘰𝘯 𝘺𝘰 (lemons). I’ll use the 𝘱𝘸𝘢𝘳𝘰 for spices and to wash meat. I like to use 𝑙𝑎𝑦 for cooking rice, bean sauce, and seasoning meat. The 𝘴𝘪𝘵𝘸𝘰𝘯 𝘺𝘰 are perfect for washing the meat because it remove the bad smell. I also use 𝘴𝘪𝘵𝘸𝘰𝘯 𝘺𝘰 to protect myself from the coronavirus. Around the apartments we have 𝘴𝘪𝘵𝘸𝘰𝘯𝘦𝘭 (lemongrass) growing. I boil the 𝘴𝘪𝘵𝘸𝘰𝘯𝘦𝘭 and 𝘴𝘪𝘵𝘸𝘰𝘯 𝘺𝘰 and drink my tea. This is what I’ve always done. I have to stay strong.” Translated from Creole by Frantzo  “You can put that I’m Felipe from Zidaza, Querétaro. Even though I moved here in ‘83, I will never forget my roots or my beloved state. There’s so much I miss from home: the food, family, and the way of life. I’ve returned to Querétaro once, but my children are here. I’ve been able to raise my family and show them the agricultural lifestyle. Everything I know about agriculture is thanks to how my parents raised me. I didn’t give my family riches, but my work gave me the opportunity to give them what they needed. I thank God for the opportunity to live in this country and see my family grow. I’ve worked in the fields with joy because it’s a job that feeds others, possibly all over the world. For those of us that work in agriculture, we are happy and proud of the work we do. We see our food grow from when it’s planted to when it’s harvested. I’ve loved everything about seeing produce begin its life and how it ends up on the tables of those that need it most. Then we follow the crops up north and do it again. I decided to stay here because this town has plenty of agricultural work and it reminds me of my hometown. There’s construction here and it pays more, but I don’t like it. I love what I do. It’s a beautiful thing. I’m thankful that farmworkers are being recognized more for what we do. We’re being taken into consideration. Before, people wouldn’t pay attention to us on the streets and it felt like we we're invisible to some. We’re humble people who treat each other with respect no matter who you are. I’m happy to share more about myself because this isn’t something people have been able to do before. I remember how poor the working conditions were and the type of living conditions we had. You had to watch your step in the trailers we rented because we were afraid to fall through the floor because of how many holes there were. I suffered, but I’m thankful my children didn’t have to suffer as much as I did. My grandkids will grow up in a different world than me. I don’t have money, but I have the most precious thing in the world: my children. Only God can take that away from me.” Felipe, a loving father, reflects on his experience growing our nation’s food over the last four decades. I was surprised to find out that he worked with my father, a crew leader, over a decade ago. He is one of many hardworking individuals in Immokalee getting up daily to provide our country with nourishment. Be sure to thank a farmworker when you see them. They deserve our respect. Felipe was surprised to be thanked for what he does, but this should be normalized. “Collier Freedom was created after Election Day 2016. I remember going to work in tears and everyone in my office felt the same way. That same day I had an annual exam scheduled and cried throughout it because the winner was against reproductive rights.

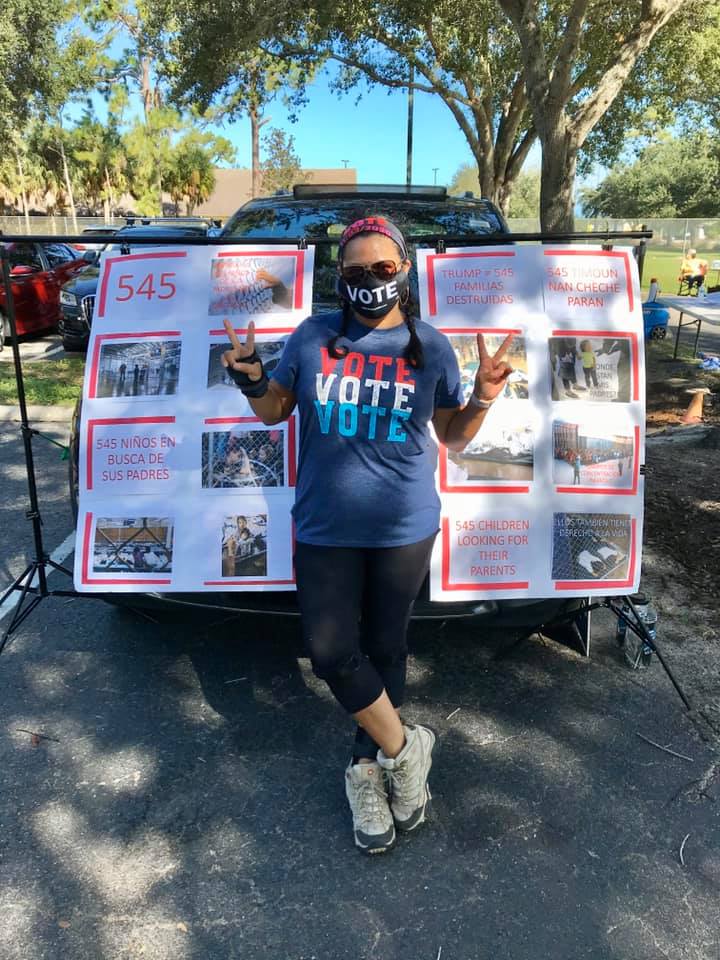

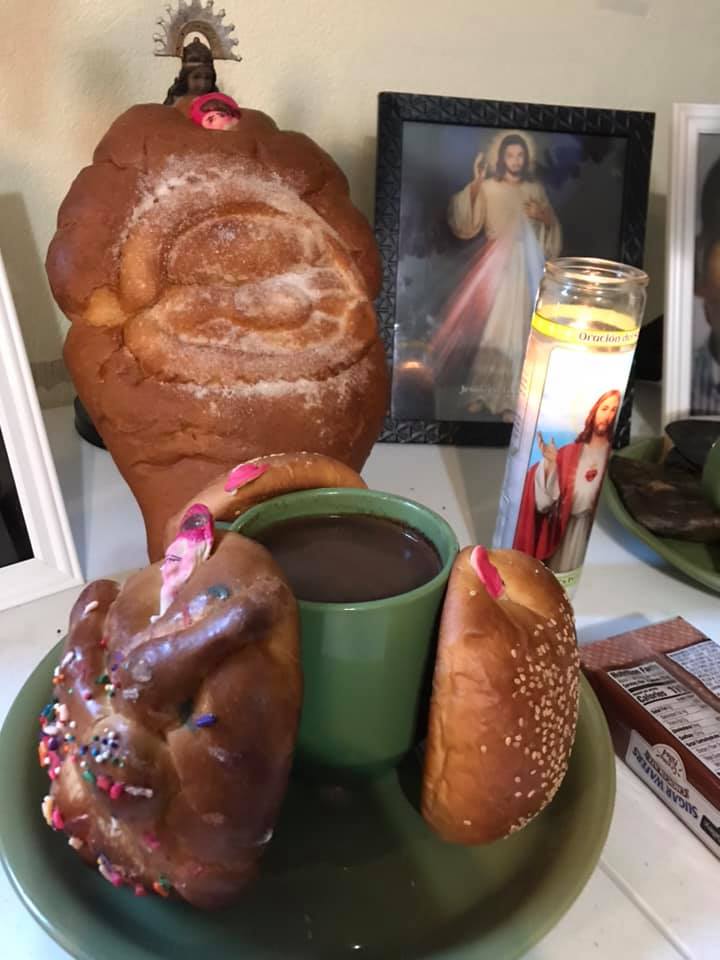

Two of my friends decided to grab dinner and beers. I realized hope helpless I felt. My friends decided that we’d march even though the results were in. Our first march was called Occupy Collier and 100 people showed up. We marched on 5th near downtown and screamed loud how opposed we were to the president-elect. People looked to us to coordinate the Women’s March in Cambiar Park. The Immokalee community is underserved and that’s why I’m voting for the candidate that represent the residents who make up the majority of the population. Other candidates for local office care more about money. On a national level, I’m personally voting for the candidate that’s not going to put children in cages. I’m also here to fight against voter suppression. I’m here for the new voters, returning felons, and those with a language barrier. I’m here to make this process less scary and welcoming for all. It’s important to stand up for these individuals so they feel they have a voice to better the community they want to be a part of. -Karynn, a local activist, reflects on why she is volunteering on Election Day in Immokalee. A steady stream of vehicles came to vote at Immokalee’s local precinct. The steady flow of voters coming in-of all backgrounds and beliefs-in Immokalee makes those volunteering and voting hopeful.  "Our parents always emphasized the importance of putting up our ofrenda (altar) to welcome our loved ones during Dias de Los Muertos. The ofrenda is how we show our loved ones we are welcoming them back with open arms. It’s not only a tradition, but a time when we have our departed loved ones visit us. My ofrenda has their favorite candy, cookies, pan de muerto, sodas, beer, nuts, and fruits. My in-laws would make it a point to stay up until midnight on the first night so our loved ones wouldn’t be alone when they crossed over to the land of the living. We make sure to have water, a candle, and path of marigold petals to guide them home. My in-laws have since passed, but we still stay up until midnight to welcome them home. I’ll turn off the candle, but I’ll pray my rosary first thing in the morning. My ofrenda wasn’t always this elaborately decorated and it could be so much more if I could find items like in Oaxaca. I have some sugar skulls that I’ve had for a few years and we started recently started planting the marigolds. My son planted some at his house and his grew to be much bigger than mine. I try to keep the tradition alive with my children. I want them to learn to make pan de muerto and put their own ofrenda when I’m gone. I tell them I’ll need somewhere to come and visit. We’ve been putting fresh tamales, homemade pan de muerto, and hot chocolate every day. I eat the bread after my loved ones have left, but we believe the taste has been taken by our loved ones visiting. Making pan de muerto has been in my family as long as I remember. My abuelito would go out and sell pan de muertos every year in Oaxaca, Mexico. He taught my mom, who eventually taught me. I’m attempting to show my kids now to keep the tradition going, but it’s challenging and time consuming. I’ve modernized my mom’s recipe a bit by using butter vs lard and adding orange extract. My bread has a unique shape with designs because I wanted them to resemble more of a body, but I still make some in the traditional shape. My eldest daughter had the most interest in learning how to make it and I hope she can carry on the tradition. Yesterday was Dia de las Visitas (Day of the Visits) and that’s what I miss most about celebrating in Mexico. We’d go to our family member’s houses and eat hot chocolate, tamales, and pan de muerto as we reminisced on old memories. We usually play music throughout the day and yesterday I played las chilenas from Oaxaca for my dad. Today is Dia De La Comida (Day of Food), a time when I make the favorite food for those on the ofrenda. I’m planning on making caldo de pollo (a traditional Mexican chicken soup) for them to enjoy. Since our departed loved ones are home visiting us, my family personally doesn’t go to the cemetery until all the celebrations have passed. There’s no reason to go if they aren’t there. When they leave us again, we’ll go and leave flowers at their graves. Right now, everyone comes to my house during this time of remembrance, but in Oaxaca, each household is expected to have their own. Mine has pictures of my in-laws and father, but I know that all of my departed loved ones are visiting me even if I don’t have their photos on the ofrenda.” Paulina, a local baker of pan de muertos (bread is the dead), reflects on the traditions and customs she inherited from her family. She also sells baked goods throughout the year and can be reached at Pau’s Bakery Our eldest sons were born at home with help from my husband. He was a big help when it came to the birthing process and taking care of me afterwards. In Guatemala, it’s customary to have home births. We went to the hospital this time for our baby boy, but it was all so different for us.

Our family lived in a small Guatemalan town surrounded by mountains and limited opportunities. Mateo and I met as kids through our families since we lived in neighboring towns. Both of our dads were absent in our lives and our childhood was tough because of it. I never got a chance to go to school because my family didn’t have money to pay for schooling and Mateo only finished second grade. Before we moved here, our oldest son only attended 4 years of school. We had to wait until he was 9 years old because we couldn’t afford it before, but it was hard to decide which of our kids we could send. We’re so happy all our children can go to school here without us worrying about which child to send to school. Life hasn’t been easy here, but we’re happy there is always work. In Guatemala, we never knew when we could work. My husband picked coffee beans and did some work as a handy man, but it was only enough to get by. I sold handmade purses and bracelets I used to crochet. As a little girl, I would sit and watch the older women in my family do the same. We miss having our mom and family surrounding us, but when you have your own family, that is your focus. We are happy as long as our kids are with us. We want more opportunities for them. Translation provided by: Maria Sebastian "Long before I followed my heart to teach in countries I had only read about as a kid, I traveled the south as my parents followed the crops.

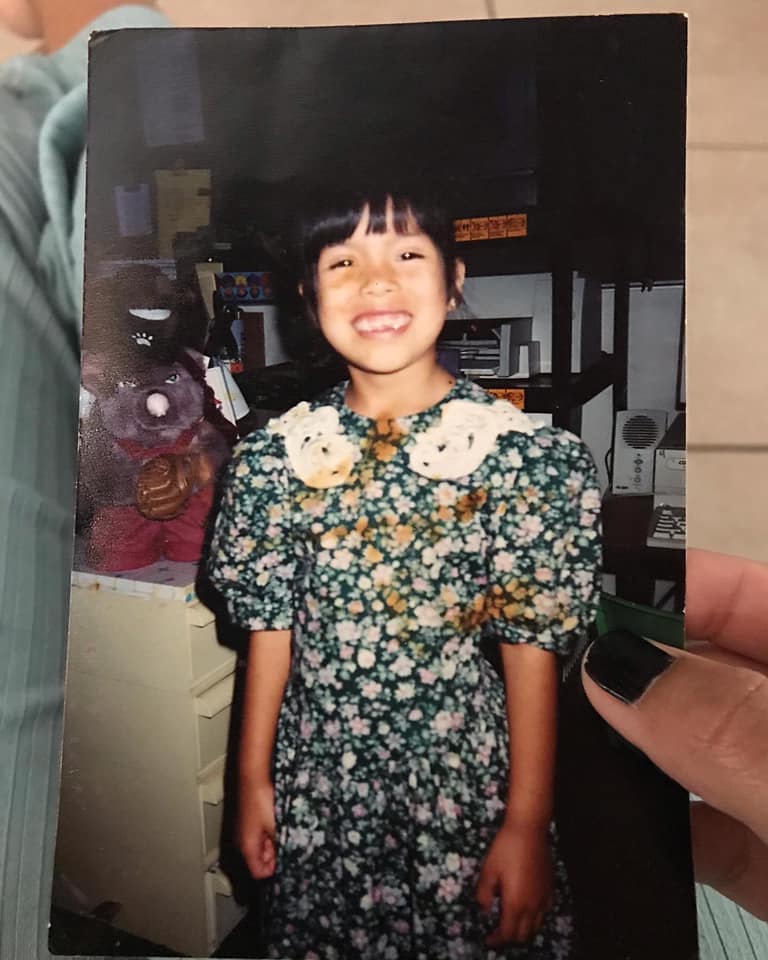

My native tongue helped me create a bridge between new migrant families and my elementary schools in the north. The responsibility to translate school enrollment forms as an 8 year old lead to the overachieving attitude I have to balance today. With raven black hair in a sea of blonde and brunette, my uniqueness was celebrated by my peers and teachers. While my differences were celebrated, my parents realized their own differences made them targets. As I grew up, I also felt my differences were a negative in the land I was born in. Years of hiding aspects of my cultural identity to assimilate to what a “true American” was supposed to act like led to shame. It’s taken a while, but I’ve been able to take back the narrative and use my mother tongue to help advocate for those in my community." -María, the founder of Roots of Immokalee, shares a snippet of her story. (3/3)I continued to do odd jobs after high school because I still had to help my family. I worked in the oil fields with Exxon Mobile for 18 months following graduation, but I started noticing the older gentlemen were missing fingers. I looked at my ten toes and ten fingers and decided it was time to move on to college. I applied for scholarships and St. Edwards University in Texas was the first one to respond.

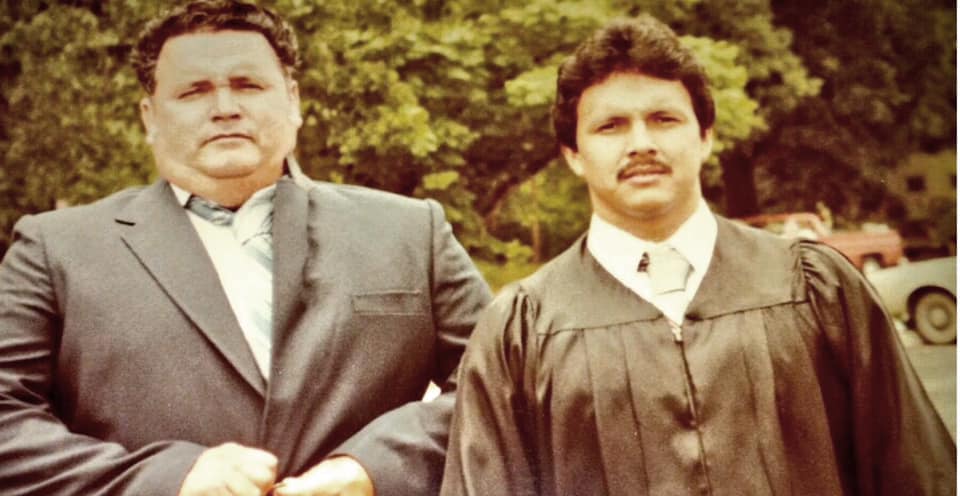

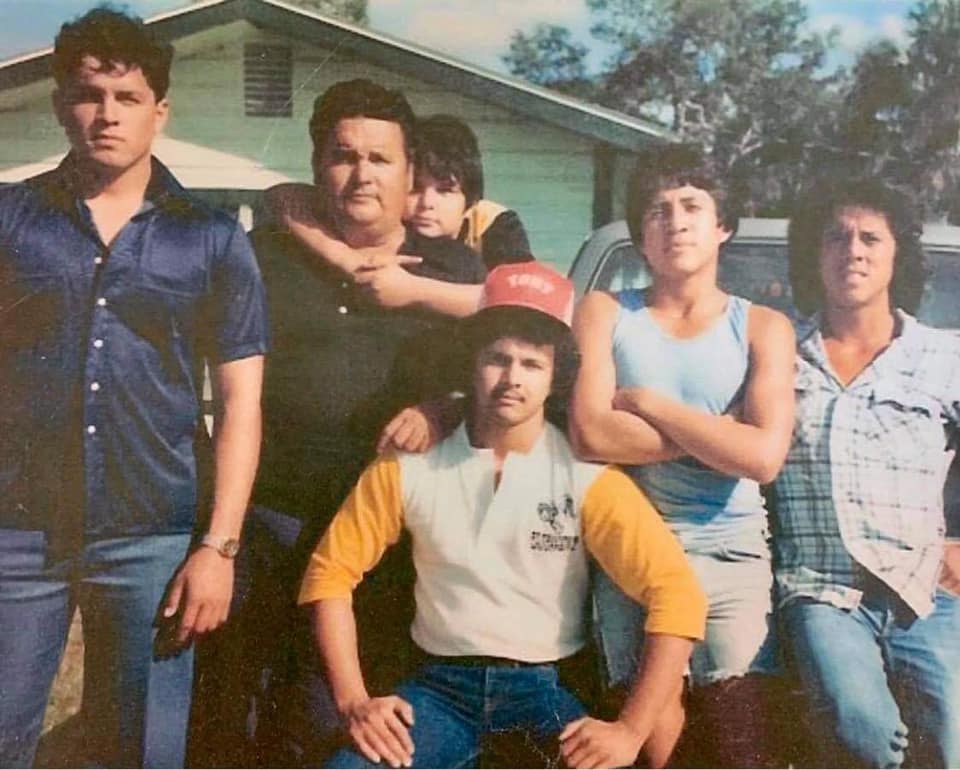

Going to school in Austin really opened my eyes to the possibilities of who I could become. When I went to the financial aid office, the Financial Aid Director was Mexican. Her husband was a controller for the city. The Chief of Police was Mexican. When I went to open a bank account, the bank’s president was Mexican. In Immokalee, 90% of businesses and leadership positions were predominantly white at that time. I took that as motivation and became a sponge. My junior and senior year, the Tribe was able to provide me with some financial aid, which was a huge help at that time. After graduation, I imagined I would be a P.E. teacher and eventually coach a sports team at the local high school since I had been so involved myself. I had just completed my final interview and was set to start teaching in 3 weeks when the newly elected President of the Seminole Tribe reached out to me. He asked me to be a part of his team in the recently built Seminole Casino. I never imagined myself in gaming, but I was sold once I learned more about gaming and our history. I didn’t learn about my Seminole and Mexican history until after college when I started working with the Tribe. It may have been because the Seminoles don’t have a written language and our history has been passed down verbally. All I knew about my culture was from what I learned from my parents and my grandparents. I didn’t learn about the Trail of Tears or even how our land was taken away. The Seminole Tribe used to be spread across Florida and lower Georgia, but by the 1850’s and 60’s, we had less than 200 members. Today we have around 4,300 Seminoles, but our language is still not written. When members of the Seminole Tribe enlisted in the military, they used that as an advantage to communicate across groups during the war just like the Navajo’s did. Luckily, these Seminole code talkers returned home. Tony, a local Seminole tribe member, reflects on his experience leaving and returning to Immokalee. (2/3)The Sugar Shack on Main Street and 9th was the hangout spot back then. Half of the building was a laundry mat and the other half served milkshakes and burgers. There was only a small seating area, but that didn’t matter because everyone hung out in the parking lot. We’d grab a bite to eat and cruise down Main Street in our cars towards the park and back for hours. After home football games, we would head to the sock hop at the community park for an hour before we headed to the Sugar Shack parking lot.

Where iTech sits today, I attended elementary school. The elementary, middle, and high school were all on the same campus. Highlands Elementary opened when I began second grade so I rode the bus there. The Bethune School was still segregated at that time. It was predominantly Black, but a few Mexican students attended. Eventually Pinecrest and Village Oaks opened. At that time, 90% of the businesses were owned by white folks. Before there was Winn-Dixie, we had Fred’s Bond, Minors, and Shopworth. I bagged groceries at Fred’s Bonds, which now is the Fiesta Supermarket. Soda and chips were only 10 cents each. If you went to the St. Clair gas station at the time I was working there, you would pay 25 cents a gallon. Back then it was full service. For only 70 cents, I would check your tires, pump your gas, and clean your windshield. There were two theaters in town, the Azteca was the Spanish theatre and The Tent was the English theatre. The Tent Theatre, owned by the Feathers’, is where I’d go watch movies with friends. Eventually they named the local clinic after the owner, Ms. Marion E. Feather. Main street even had a high-end jewelry store where Mimi’s Pinatas is at today. A freight train would run through town to deliver shipments to Everglades City. You’d hear the train around 6 in the afternoon. The tomatoes that were picked by farmworkers in the community such as my dad and uncles were peeled and packaged at the local tomato canning factory that my mom worked at. She would also cook meals for other farmworkers to make extra money. My parents were both hard workers. My dad would tell us to make a living with our head and not our back. He pushed for us to do good in school and get involved. When I wasn’t working, I would play football, basketball, and eventually wrestling when it was first offered in 1976, my senior year. Some of my favorite memories during that time were the Harvest Festival and how lit up Main Street was during the holidays. The high school marching bands would come from all over including Labelle, Clewiston, and Cape Coral. We’d enjoy our BBQ as we watched the rodeo and pageant. We celebrated that Immokalee was the Watermelon Capital of the World at that time. Tony, a local member of the Seminole Tribe, reflects on the changes in the Immokalee Community. “After my mom passed away, I took over her mini supermarket stall. It was a lot of responsibility at 9 years old, but I had to care for my family. Our stall was similar to the farmer’s market here in town except we didn’t pay rent. A wealthier man in town owned the land and allowed us to set up our stalls because he wanted people to better their lives. My business gave me a sense of purpose and helped care for my family.

When I came to the U.S. in 1986, I let my business go. You needed a permit here. Things were different. I started working in the packing houses packing every kind of vegetable that was in season. I eventually was able to work in other industries, but I had an accident at my last job that left me to take care of the home and garden. I was my own boss in Haiti and I want my daughters to do the same. I have tried to instill the same mindset in my daughters because I know the value of being your own person and boss.” Claire, a retired business owner, spends her time gardening and caring for her family. |

AuthorMaria Plata is a Mexican-American writer, educator, and lover of connecting people through storytelling. Archives

March 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed